‘ENSURING THE CONTAINER IS STRONG’ – REGENERATING URBAN MAURI THROUGH WĀNANGA

Desna Whaanga-Schollum (Rongomaiwahine, Kahungunu, Pahauwera), Caroline Robinson, Keriata Stuart (Te Āti Awa), Biddy Livesey with Bill Reed

More than three hundred years ago, tupuna of the Taranaki iwi of Aotearoa New Zealand carved marks to put mauri, an intangible spiritual essence, into free-standing stones or living rock. Lines drawn between these taonga created an eco-philosophical container, acknowledging tribal responsibility and authority, or mana whenua, for the area bounded within.

In Te Ao Māori, mauri – the regenerative life-principle - connects people and spirit to all within the natural physical world. Taonga, in the form of highly valued created objects, carry the mauri of the maker/s. The challenge for contemporary Māori designers and creatives is to strengthen and restore that spirit of connectivity and value in the densely occupied, rapidly evolving urban landscape. The concept of ‘Urban Mauri’ asks:

‘What methods might be utilised in professional practice to regenerate mauri in an ephemeral existence, cultivating reconnection in our day-to-day lives within personal, social, cultural and environmental contexts?’

The authors of this article are Māori and tauiwi researchers, designers, artists and facilitators. We initiated exploration of Urban Mauri through a wānanga held in Tāmaki Makaurau in November 2014. Co-produced by Ngā Aho (Network of Māori Design Professionals) with ‘Regenerative Practice’ expert Bill Reed of Regenesis Group, the wānanga called together participants under the kaupapa of: “’Urban Mauri’ - Designing Tāmaki Makaurau - connecting cultures. We seek to integrate arts and culture into our everyday lives. Support sustainable development of Māori outcomes, leadership, community and partnerships. Acknowledge that people and nature are inseparable.” Regenerative practice frameworks were employed within a wānanga ‘container’ of learning. Similarities were drawn between the two design languages used respectively by Māori creatives and by regenerative design practitioners. Concepts from Te Ao Māori and regenerative design were both seen to be centred within living systems understandings, and have potentiating power to generate and nourish mauri in contemporary co-design practice. This article explores some of that potential.

Mauri – classifying the unclassifiable

Mauri is a central concept in the Māori world, but to define it is to attempt a ‘classification of the unclassifiable’ (Holman 2007, p.15). Like other deep traditional concepts, mauri has undergone a continual “process of re-invention and expansion” (Holman, 2007, p.4). Most contemporary discourse about mauri draws on the late Rev. Māori Marsden, who described mauri as ‘the bonding element that holds the fabric of the universe together’, ‘a force or energy mediated by hauora – the breath of the spirit of life’ (Royal, 2003, p.174).

Mauri can be embodied in people, natural objects and human creations. Colonial anthropologists saw ‘mauri stones’ around villages and gardens (Best, 1900), and recorded karakia such as ‘Ka te tupu koe i tō mauri ora hai’, ‘Grow by your living mauri’. Holman (2007, p.337) sees these as invocations to Rongo, the atua of cultivations, to release the ‘potentiating power inherent in the growth of the crop’. Contemporary Māori continue mauri practices, such as often including a mauri stone in new meeting houses. Barlow (1991) describes this mauri as “the power obtained through a covenant with the gods to take care of the house and to fulfill the wishes, desire and hopes of the people who will use it for noble purposes.”

Through human actions, mauri can also be embodied in a community or place (Royal, n.d.). Kepa Morgan (2011) has designed the ‘Mauri-o-meter’ as a holistic assessment tool for environmental kaitiaki, evaluating the potential of a development proposal to restore or denigrate the mauri of the people and the location. The ‘Mauri-o-meter’ uses the term mauri to discuss a place’s life essence, with kaitiakitanga being an active practice of guardianship by tangata whenua.

As contemporary creators exploring the concept of mauri through our practice, we reconnect to the ancestral knowledge of our tupuna who drew on their wairua and mana, to activate created objects and spaces with mauri. We may express mauri in very different physical and social environments today, but the continuity is evident in practices of respect, reciprocity and regeneration.

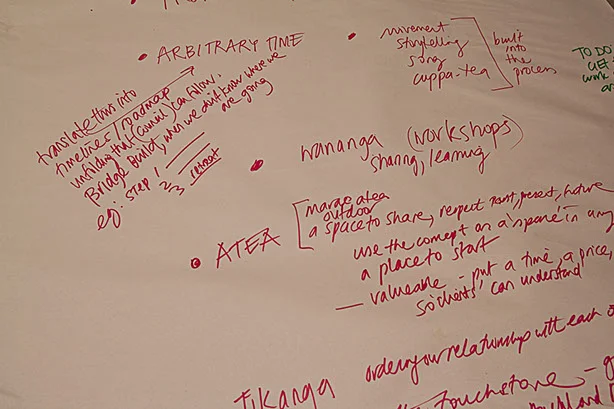

Scribed Kōrero. Urban Mauri Workshop 2014

Regenerative practice

The work of regeneration is described by Pamela Mang and Bill Reed of Regenesis Group as‘… the continual evolution of culture in relationship to the evolution of life’ (Mang, P and Reed, B, 2012, p.26). To be regenerative in this sense recognises that human and more-than-human worlds are totally interdependent, and that we have a role to play, consciously working within life’s transformational processes of birth, life, death and rebirth to help grow potential. With a strong focus on relationships, the regenerative design and development methodology developed by Regenesis Group engages at multiple levels, including the level of the individual person, the project, the community, the watershed, as well as the larger socio-ecological context.

Lived experience and story are key to this approach. The diverse and complex relationships between people and place cannot be understood in the same way a mechanical system might be, in terms of a check list or collection of parts. Neither is design process seen as problem solving for any one cause or issue. The aim is to recognise and engage meaningfully within the seen and unseen realities of the whole living system.

Through whole systems frameworks, and a process called ‘story of place’, Regenesis help people and the land to talk to one another, so that the patterns of relationship are revealed. This process of shared research and experience connects people and place ‘essence to essence’. Facilitators work alongside key community participants to

“… uncover the core patterns of the place, to develop understanding, and to fall in love. We're learning with each other, we're co-discovering”

(Bill Reed in Ngā Aho, 2014). This place-sourced, connective, co-creative methodology, can innovate meaningful change at all scales, including city and even nation scale.

A regenerative practice in Aotearoa New Zealand actively connects life-principle and potential from within our unique cultural partnerships, and the distinct genealogies of our sea, sky, geology, flora and fauna, informing an approach to design process unlike that of any other place.

Māori Design – an active practice of kaitiakitanga

As a result of colonisation, industrialisation, and urbanisation of much of Aotearoa New Zealand, regenerative and connective knowledge principles, such as mauri, have diminished within Māori society. Many Māori have become disconnected from their indigenous realities. Marsden (Royal, 2003) contrasted the Māori world with what he called “metropolitan culture”, characterised by macro-scale aggregation of people, and by secular and spiritual disconnection. Urban communities are infinitely larger than anything our ancestors envisaged; urban Māori may not be principally connected by common ancestry, as our ancestors were in early Māori settlements, but rather through contemporary societal structures such as shared places of education, work, or cultural connection.

Within the last decade, significant efforts have been made by a small but active group of Māori design professionals and researchers to articulate principles and perspectives on design in the built landscape (Awatere, Pauling, Rolleston, Hoskins, & Wixon, 2008; Awatere, Rolleston, & Pauling, 2010; Rolleston & Awatere, 2009; Stuart & Thompson-Fawcett, 2 010; Awatere et al., 2011). Focusing on the relationship between kaitiakitanga and development of the built landscape, a key success has been the promotion of Te Aranga Māori Design principles in Auckland Council’s Auckland Design Manual (te Aranga, 2014).

The Te Aranga principles focus on enhancing outcomes for the environment and ‘sense of place’, through culturally connected design.

‘Sense of place’ in this context is understood as a person or community’s appreciation of, and connections within, the special and unique qualities of their neighbourhood, city or environment that is different from other places.

The concept of Urban Mauri offers the urban creative community (mana whenua, mataawaka, tauiwi, and manuhiri) in Aotearoa New Zealand an opportunity to re-activate the ethos of reciprocity between people and land, deepening connections to ‘sense of place’. In the urban landscape it can be a challenge to understand that indigenous eco-philosophical realities exist. Ancestral indigenous identities, acknowledged through physical features, natural resources or boundary markers are often hidden, removed or built over through ongoing development. The concept of mauri as a way of being and a way of working, breaks down industrialist ideas of duality and the separation of humans and nature, linking human scale – mauri of the individual – to the mauri of a building, a neighbourhood, or an urban landscape. By recognizing the value in connective creative practice, mauri is an aligning cultural concept that counters fragmentation, isolation, disconnection and disparity in metropolitan culture.

Regenerating urban mauri through wānanga

We have chosen to explore the concept of Urban Mauri through the practice of wānanga. Historically, whare wānanga were schools of learning where highly valued oral traditions, lore and mauri were preserved and passed onto those rangatira who were considered to have the aptitude to cope. As with many terms and understandings within Māori society, researchers and practitioners have re-interpreted the term to fit new applications within the contemporary context. The practice of contemporary wānanga is derived from tikanga Māori, the act of interpreting and practising Māori knowledge. Used to describe a space or forum for immersive learning, contemporary wānanga are Māori-led events based on core cultural values, with tāngata whenua worldviews central in the discussion.

Both tikanga Māori and regenerative practice emphasise that carefully designing the process through which new knowledge is collectively generated is critical.

Considering tikanga, Hirini Moko Mead has observed that ‘[p]rocesses, procedures and consultation need to be correct so that in the end everyone who is connected with the project is enriched, empowered, enlightened and glad to have been a part of it (2003, p.318).

Wānanga can be an effective focused cultural methodology when used as the ‘container’ for aligning purpose, co-evolving new knowledge, and intentionally regenerating mauri. Wānanga can be utilised to create a resonant ‘container’ for place-based co-design, valuing personal contribution and identity, as well as for establishing and sustaining strong relationships.

If designed and facilitated for an integrative dynamic, wānanga can build productive working relationships between tāngata whenua who maintain knowledge about a specific place, and those whose practice connects with that place. Inviting people to wānanga acknowledges their self-determination and knowledge value, and gives the design process integrity. Within Māori methods such as wānanga, participants ‘place Māori experience at the centre’ and ‘wholeheartedly accept Māori processes as the reality’ (Cunningham, 2000, p66). Acknowledging value and mauri in this way can strengthen connection to place, while respecting the different roles of tāngata whenua and their manuhiri. Skillfully facilitated wānanga provide a forum where different perspectives can be understood and integrated into a more holistic understanding of a project’s aims and methods.

Whakawhanaungatanga - Identity with integrity

We believe that design processes that regenerate mauri must be based on strong relationships. Whakawhanaungatanga is a process of establishing relationships, and developing and maintaining these connections through shared knowledge and experiences. Whakawhanaungatanga allows practitioners to ‘understand themselves to be involved somatically in the process; that is physically, ethically, morally and spiritually’ (Bishop and Glynn 1999, pp.169-170). The principle of activating and renewing kinship is also at the heart of a regenerative design and development practice, which typically brings people together early in a project, giving space to build relationships and shared purpose, before design begins.

The ‘Urban Mauri’ wānanga began with in-depth introductions, in which Māori participants shared their tribal connections, while Pākehā participants identified their home in Aotearoa New Zealand, and often the origins of their settler ancestors.

This process offered an opportunity for participants to identify themselves, to reflect on their worldview, to articulate their perspective, and to consider their connections to the place, the design process and Aotearoa New Zealand as a whole.

For example, community leader Tamati Patuwai greeted other participants with the observation that '[al]though my ancestors are here, these feet, these hands, and this body here come from the east side of Auckland. So it's a pleasure to be back amongst Te Kawerau a Maki, Te Tao Ū, Tainui waka over here, Mahuhu-ki-te-rangi up there, Ngātokimatawhaorua over here… just a pleasure' (Tamati Patuwai in Ngā Aho 2014). These kinds of greetings have reference to the concept of mauri by acknowledging and celebrating the intertwined relationship of the positive energy of the speaker, community, place, and the relational whakapapa of identity that connects them.

Mana - Personalizing responsibility and respect

Within the design process, we emphasise personal accountability for access to and use of knowledge. When working with Māori or as Māori, we know that consent is not so much given for a project or a specific set of questions, but for a person, for their credibility. Consent indicates trust and the assumption is that the trust will not only be reciprocated but constantly negotiated - a dynamic relationship rather than a static decision' (Smith, 2012, p.137). The Te Aranga Māori Design Principles emphasise mana, a concept that, in the design context, provides ‘a platform for working relationships where mana whenua values, world views, tikanga, cultural narratives and visual identity can be appropriately expressed in the design environment’ (Te Aranga, 2014). A designer working with Māori knowledge and custom enters a relationship with the guardians of that knowledge, and retains a personal responsibility for ensuring that knowledge is respected.

The design process itself must also be credible and responsive, in order to be capable of respecting cultural knowledge and harnessing all vital contributions. ‘Integrative Design Process’ is a framework often used within regenerative practice. As a structure and discipline of iterative inquiry, the integrative process can embrace diverse participation and facilitate genuine engagement with inherent difficulty, mystery and paradox. This practice holds different and opposing ideas in an atmosphere of trust, recognizing that valuable efficiencies and potential is to be found in reconciling diversity. And conversely, that avoiding this complexity typically results in a combative dynamic between participants, and ultimately a compromised and therefore wasteful design outcome.

Energized Kōrero. Urban Mauri Workshop 2014

Discussing their current professional practices, the Urban Mauri wānanga participants identified barriers to achieving creative eco-philosophical potential. Participants felt that they often operated in isolation with little opportunity for depth in discussion of beliefs, goals and alignment of purpose in their professional practices. Invitations to operate in a collaborative and reflective manner were not obvious within typical project situations, and investing in deeper conversations could be seen as taking too much time and resource within tight timelines and budgets.

In this context, the wānanga process was seen to effectively assist with integrating and strengthening conscious relationships that recognised, valued and harnessed the mana, skills and knowledge held by different parties.

Aligning purpose and a wider consciousness of skills and experience generates synergies, which over the longer duration of a given project provide the basis for activating a productive, meaningful and more efficient co-design practice.

Urban Mauri - “Strengthening the container”

Acknowledging the diversity of people present, participants in ‘Urban Mauri’ felt that the fusion of wānanga with regenerative, living systems design process, created a powerful opportunity to grow meaningful co-creation between tāngata whenua and manuhiri; Māori and tauiwi worldviews; experienced and fledgling practitioners; professionals and community. Embracing diverse identity, and consequently, personal subjectivity, is central to developing a design process with integrity. Respectful and reciprocal wānanga provides a forum where different histories, knowledges, and worldviews (whether religious, cultural, or practice-based) can be shared to produce a creative space in a collaborative working relationship (Jones & Jenkins, 2008). Out of confident identities, reflecting mana, and strong working relationships based in whakawhanaungatanga, a much richer collective understanding of ‘how life works’ in each unique place becomes available. This understanding tangibly informs practitioners how to regenerate mauri through design practice.

Within the Urban Mauri wānanga, participants experienced a conscious cultural process that embraced complexity, enabling productive cross-cultural dialogue and acknowledging a collective desire to move towards mauri ora - healthy cultural identity. A repeated image in the Urban Mauri wānanga was of a container into which participants could channel energy, offering their mauri into the event as our ancestors imbued it in their creations. Participants at the wānanga agreed that, as a city, Tāmaki Makaurau is poised to create healthy, place-specific identities in a truly unique way.

Tāngata whenua have a sense of belonging, of home as a ‘place to stand’ that facilitates deep connection within our world. The concept of Urban Mauri offers practitioners an indigenous way to be innovative and regenerative in their approach, connecting people, place, purpose and practice to yield valuable holistic outcomes. Utilizing wānanga as a design process grounded in Māori understandings of relationships and identity contributes to regenerating mauri through welcoming people into spaces in a way that connects through both the senses and the stories of the urban landscape.

To the readership:

How do you see yourself, as an individual, and as a practitioner, connecting to the mauri of your urban landscapes?

Glossary of Māori terms

Atua: God, supernatural being

Hauora: The breath of the spirit of life; wellbeing

Iwi: Tribe or nation

Kaitiaki: "Guardian, used here in the context of a representative of the tribal group with responsibilities for looking after the land; also the action of such caring"

Kaitiakitanga: The practice of kaitiaki

Karakia: ncantation, ritual chant

Kaupapa : Topic, policy, matter for discussion, plan, purpose, scheme, proposal, agenda, subject, programme, theme, issue, initiative

Mana: Responsibility, authority or prestige, spiritual gift

Mana whenua Authority and responsibility derived from ancestral land

Manuhiri: Visitor, guest(Williams)

Māori: Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand

Mataawaka: Non-mana whenua Māori migrants and descendants who have moved away from their traditional homes

Pākehā: New Zealander/s of European descent

Rangatira: Chief or leader

Rangatiratanga: The practice of being rangatira. Sovereignty, chieftainship, leadership, self-determination or self-management

Tangata whenua: People of the land

Taonga: Treasure, anything prized (Moorfield)

Tauiwi: Non-Māori (Moorfield)

Tikanga: Māori practices and customs, established over time, and often specific to a tribe or place

Tupuna: Ancestors, grandparents

Whakapapa: Genealogy, line of descent

Wānanga: A Māori place of or event for learning, particularly one dedicated to considering traditional knowledge.

Wairua: Soul or spirit (Williams)

Whanaungatanga: Relationship, kinship, sense of family connection

References

Awatere, S., Harmsworth, G., Rolleston, S., Pauling, C., Morgan, T. K., & Hoskins, R. (2011). Kaitiakitanga o ngā ngahere pōhatu: Kaitiakitanga of urban settlements Hamilton, New Zealand: Landcare Research - Manaaki Whenua.

Awatere, S., Pauling, C., Rolleston, S., Hoskins, R., & Wixon, K. (2008). Tū Whare Ora - Building Capacity for Māori Driven Design in Sustainable Settlement Development. Hamilton, New Zealand: Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd.

Awatere, S., Rolleston, S., & Pauling, C. (2010). Developing Māori urban design principles In K. Stuart & M. Thompson-Fawcett (Eds.), Tāone tupu ora: Indigenous knowledge and sustainable urban design. Wellington, New Zealand: Steele Roberts.

Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Māori culture: Auckland, N.Z. : Oxford University Press, 1991.

Best, E. (1900). Spiritual concepts of the Māori. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 9(4, 173-199. Retrieved from http://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document//Volume_9_1900/Volume_9,_No._4,_December_1900/Spiritual_concepts_of_the_Maori,_by_Elsdon_Best,_p_173-199/p1

Bishop, R., & Glynn, T. (1999). Researching in Maori contexts: An interpretation of participatory consciousness. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 20(2), 167.

Cunningham, C. (2000). A framework for addressing Māori knowledge in research, science and technology. Pacific Health Dialog, 7(1), 62-69.

Holman, J. P. (2007). Best of both worlds: Elsdon Best and the metamorphosis of Māori spirituality. Te painga rawa o ngā ao rua: Te Peehi me te putanga ko o te wairua Māori. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Māori in the University of Canterbury. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10092/939

Jones, A., & Jenkins, K. (2008). Rethinking collaboration - Working the indigene-colonizer hyphen. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies (pp. 471-486). Los Angeles: Sage.

Mang, P and Reed, B. (2012). Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Building Research & Information, 40:1 23-38, p26

Mead, S. M. (2003). Tikanga Māori : living by Māori values / Hirini Moko Mead: Wellington, N.Z.: Huia Press.

Morgan, T. K. K. B. (2011). Waiora and cultural identity. Water quality assessment using the Mauri Model. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 3(1).

Ngā Aho. (2014). Notes - Urban Mauri wānanga held November 14 2014, Blockhouse Bay Boat Club. Auckland, New Zealand.

Rolleston, S., & Awatere, S. (2009). Nga hua papakainga: Habitation design principles. MAI Review, 2(Article 2), 1-13.

Royal, T.C. (n.d.) Te Ao Mārama – the natural world - Mana, tapu and mauri. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/te-ao-marama-the-natural-world/page-5

Royal, T.C (Ed.). (2003). The Woven Universe: Selected Writings of Rev. Māori Marsden. Wellington: MKTA-Living Universe Ltd.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed). Dunedin, N.Z.: Otago University Press.

Stuart, K., & Thompson-Fawcett, M. (2010). Tāone tupu ora : indigenous knowledge and sustainable urban design / edited by Keriata Stuart & Michelle Thompson-Fawcett: Wellington, N.Z. : Steele Roberts, 2010.

Te Aranga. (2014). Te Aranga Principles. Auckand Design Manual. Retrieved from http://www.aucklanddesignmanual.co.nz/design-thinking/maori-design/te_aranga_principles