LARGE PARKS AND BIG CITIES

Mario Schjetnan

Any great city has memorable parks providing them with identity and structure, and establishing equilibrium with its built areas, enabling places for gathering, entertainment, recreation and relaxation.

Our favorite cities, those we love to visit or like more contain a great variety of open spaces and provide their citizens and visitors with spaces to stroll among trees intrails, walks, promenades, docks, lakes and rivers, large grassland fields, play areas, places for gathering or, in contrast, for solitude, reflection and the contemplation of beauty.

Jardín Natura, Francisco Gómez Sosa

Large Urban parks have an enourmous variety of functions. They are popularly characterized as "lungs of the city", or places "where the city breaths"; through its large tree masses they produce oxygen; they also infiltrate water into the aquifer and provide habitats for biodiversity of many species. Ecologists have determined them as "environmental services", which rationally establishes accountability in ecological balance within the urban ecology of cities. (1)

In urbanist terms they provide structure and form to the city. Le Corbusier defined the term "conforming magnitude and congruous dimension", meaning equilibrium of scale in proportion to the dimnsion of city or building. It is a dialogue between the void and mass that establishes form, structure, order and sustainability.

In our colonial cities in Latin America, plazas, gardens and small parks were provided within a chequered reticulate pattern, alternating voids to solids among city bolcks, this established sequences of urban tissue with alternating small parks. But it is in the contemporary city -more complex, dense and chaotic- where large parks are fundamental in the spatial structure of the city.

If small parks and gardens or public forests (outside the city) have existed since antiquity, it is in the modern city where large urban parks were introduced as a socialand natural factor, as an element of common accesibility, providing public and democratic space. The modern park emerges as a social necessity under the conditions of overcrowding and sanitary conditions due to sudden migration of workers from rural territories to urban settlements. (2)

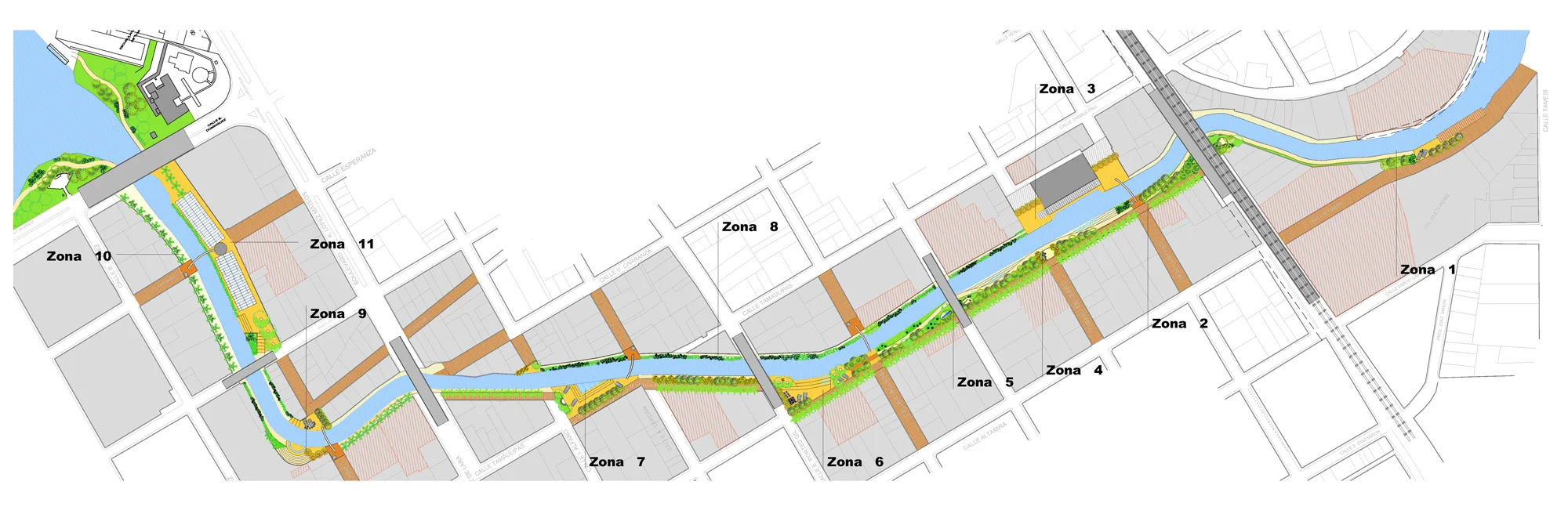

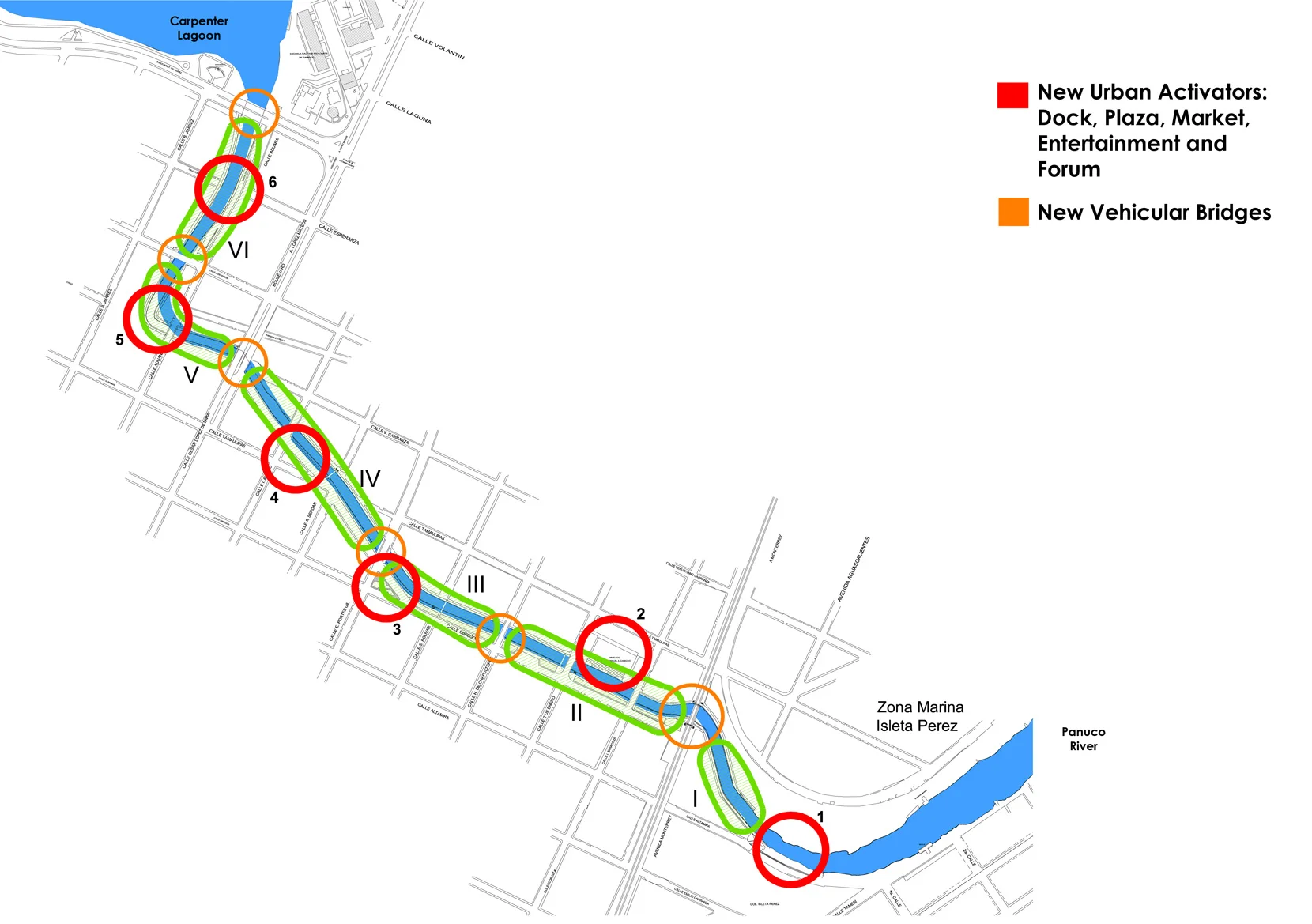

Canal de la Cortadura Lámina 3

It started with the rapid expansion of cities in the early and mid- XIX century in Europe and the United States and continued in the XX century in the rest of the world. And will continue through the first half of XXIcentury as demonstrated by the emergence of innumerable metropolis with populations of 10 million people or more in all five continents of the world. Two thirds of the world population will live in cities by 2050. More than half the current population already does. (3)

Central Park and Prospect Park in New York; Bois de Boulogne and Vincennes in Paris; Hyde Park and Regent´s Park in London; Tiergarten in Berlin are the first large urban parks for the people and are still reference and emblematic icons of these great cities. In these modern parks the differencial characteristic as opposed to large public spaces such as the Tulleries (where rich people strolled to see and be seen) were now "centers of outdoor activities", such as the family picnic; cycling, trotting, walking, riding, informal and formal sports, etc. And also passive activities among trees, turf and lakesconducted to the contemplation and enjoyment of nature. Soon these models were replicated around the world and also in Latin America: Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Rio or Sao Paulo.

Frederick Law Olmsted, wrote that parks and natural areas in the city would civilize the american citizen, integrating them to an urban culture of conviviality, respect and identity. (4)

It has been demonstrated today in scientific papers and investigations that parks generate conviviality and reduce violence; that parks, if properly managed and mantained are elements of equity and improve substantially the quality of life. More research has demostrated that people crossing parks to and from work are more productive and get home with less stress and anxiety. (5)

The contemporary large urban park of today is emerging from the recycling and transformation of the post-industrial city or the "naturation" of large infrastructural artifacts such as channels, reconverting the unidimensional condition of drainage, flood control or electricity lines or railroads into large, continuous linear parks. In addition, large areas of dereliction or refuse are being converted into new urban parks. (6)

These new trend in the evolution-transformation of cities around the world have demanded landscape architects to form teams with urbanists, ecologists, engineers, soil mechanics and chemical scientists to participate in these exciting, transformative and regenerative, large urban tracts. They have opened new dimensions and opportunities for landscape architects to a new leadership in the design and configuration of the city. (7)

Following, are a few recent park examples executed by my office, Grupo de Diseño Urbano in Mexico City and Puebla (100 miles east of Mexico City).

Chapultepec Park Rehabilitation. (2004-2009and 2013 -present).

This is probably the oldest park in the Americas. There is evidence of interventions by Nezahualcoyotl as designer for Moctezuma´s gardens since 1460. In 1530 the spanish king Carlos V, declared Chapultepec as natural forest park for Mexico City. The present day Chapultepec Park was redesigned and transformed from 1906 and re-opened in 1910. The three sections of the parkconstitute an area of 686 hectares.

Due to its excessive centrality (10 museums)and accesibility (five metro stations) , Chapultepec had suffered a progressive decay, particularly in its green and forested areas, in infrastructure, lakes and services and in the uncontrolled incorporation of 1400 informal vendors. The rehabilitation of Chapultepec is a citizen´s initiative with a Citizen´s Council, a Donors Board and the city authorities.

This is a project of restoration and rehabilitation although several new interventions by our office are the Botanical Garden and the Promenade Fountain between the Anthropological Museum and the Tamayo Museum of Art. And recently, to be opened in the Second Section of the Park, a redesigned circuit for bycicles, running, electric bus transportation and a new forested promenade, the first major project within the Master Plan.

Bicentennial Park at the old PEMEX refinery in Azcapotzalco, Mexico City. (2007-2012)

With an area of 55 Hectares, the former Azapotzalco PEMEX refinery has been transformed into a highly diversified urban park in the north east section of the metropolitan area of Mexico City. One of the most interesting sections of the park has been the Nature Botanical Garden, where seven of Mexico´s biomes have been included, with a Chinampa and Ochid House. The Botanical Garden was built over pre-existing concrete slabs with several bioclimatic structures for the diverse ecosystems. The orchid house was built within a former cistern of 100x15x5 m., where several ramps and decks drivevisitors to a new magical natural environment. Bicentennial Park attracts 2 million visitors per year.

Canal de la Cortadura, Linear Park, Promenade and Waterway. Tampico, Tamaulipas. Mexico. (2004-2015).

This recently finished first stage project, which took more than 10 years to be built and will continue, to probably be finished in its second stage in 2016. The Canal de la Cortadura project can be recognized as an urban integral transformation, where an old infrastructure channel is converted into a linear park, promenade and waterway. New vehicle and pedestria bridges were designed and built, a new channel, wider and deeper, and a continuous lienear park has been developed to rehabilitate a very deppressed area of the central part of the City port of Tampico, on the Gulf of Mexico.

NOTES

(1) See Nina- Marie Listerin "Sustainable Large Parks: Ecological Design or Designer Ecology" in Large Parks edited by Julia Czernak and George Hargreaves" Princeton Architectural Press and GSD Harvard. 2007.

See also "Parklets Are Great, But Big Parks Pack a Big Punch" by Cassie Owens in The Landscape Report, ASLA. September 1, 2015 ("But the key point is: If you don´t include large contiguous green spaces, then you´re probably not going to be providing a), as high amount of ecosystem services as you could and b), as many ecosystem services as you could". Iain Sott)

(2) See Leonardo Benevolo in the "Origins of Town Planning" MIT Press. 1971

(3) See "The Speed of Urban Change" and " Where the Big Cities Are" (Maps) in "The Urban Age Project" by Ricky Burdett and Philip Rode. in the book "The Endless City". Phaidon. 2009.

(4) See Fredeick Law Olmsted in "Public Parks and the Enlargement of Towns" in "Civilizing American Cities: a Selection of Frederick Law Olmsted´s writings on City Landscapes" Edited by S.B. Sutton. MIT press. 1971

(5) See "How Trees Calm Us Down" by Alex Hutchinson in the New Yorker, July 23, 2015 Towns". Citing Marc Berman of the University of Chicago.

(6) See "The Post-Industrial City: Growing Inward" by Mario Schjetnan G., in "Mexico City: Between Geometry and Geography" Felipe Correa and Carlos Garciavelez Alfaro. Applied Research + Design Publishing Harvard University. David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

(7) See"Speculating on Size" by Julia Czernak op. cit.