PAPER: DRAWING AS A FUNDAMENTAL TOOL FOR THINKING IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

Abstract

This paper considers the role of drawing and representation as a tool for capturing the more ephemeral aspects of the landscape. These aspects include ideas about change, chance and transformation. The importance of drawing has a relationship with current theory related to emergence, shifting social norms around material landscapes and an increasing drive for responsive landscapes. Several techniques drawn from the fine arts are discussed and evaluated in terms of their merits for revealing the often hidden potentials in any given landscape. The paper concludes that utilising some or all of these techniques could help landscape architects to do design that avoids an ‘off the shelf’ approach and posits that the way landscape architects understand the landscape through drawing and representation can have a significant impact on designed outcomes.

Griffiths, C.P, Drawing of How the Situation is Working, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.54

Introduction

“Landscape and image are inseparable. Without image there is no such thing as landscape, only unmediated environment.”1James Corner, theorist and landscape practitioner, goes on to say that “how one images the world literally conditions how reality is both conceptualised and shaped”.2So, what does Corner mean by this statement…does he mean that how the world is viewed conditions how design is done, or does he mean that representational variations can lead to different ways of designing, or does he simply mean that landscape architecture is a discipline based in imagery?

There are some good examples of experimentation in landscape architectural representation and some interesting protagonists for representational devices that attempt to reveal the more ephemeral qualities of the landscape. These include Eva Gustavsson, landscape architect and formally lecturer at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, who states that “The aim of aesthetic studies would be not to provide definitive answers regarding aesthetics and meaning but instead to sharpen the potential of aesthetics as a critical, central and philosophically substantiated aspect of landscape architectural research and practice.”3

Recently at an annual meeting of landscape architects organised by the Auckland Branch of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects (a two slide, two minute presentation) several points to consider became apparent. These included the proliferation of normative representational strategies that reduced the range of extremely interesting and varied projects to static snapshot visuals, these were in the main plan, section or perspective representations. This event is a social and informal gathering where landscape architects have the opportunity to share what’s going on in the respective Auckland firms. Even in this context the profession struggled to capture the poetry, the fluidity and the dynamism of new landscape projects that have real potential to contribute to the growth and development of Auckland City. Priority is often afforded to the representation of a conclusion of a landscape scheme and often little account is given of arguably, the most useful type of representation; drawings which enable the ‘landscape architecture’ to develop and emerge. This focus seems apt to produce designs that foreground object-formation processes, these are perhaps less able to respond to the flux of life.

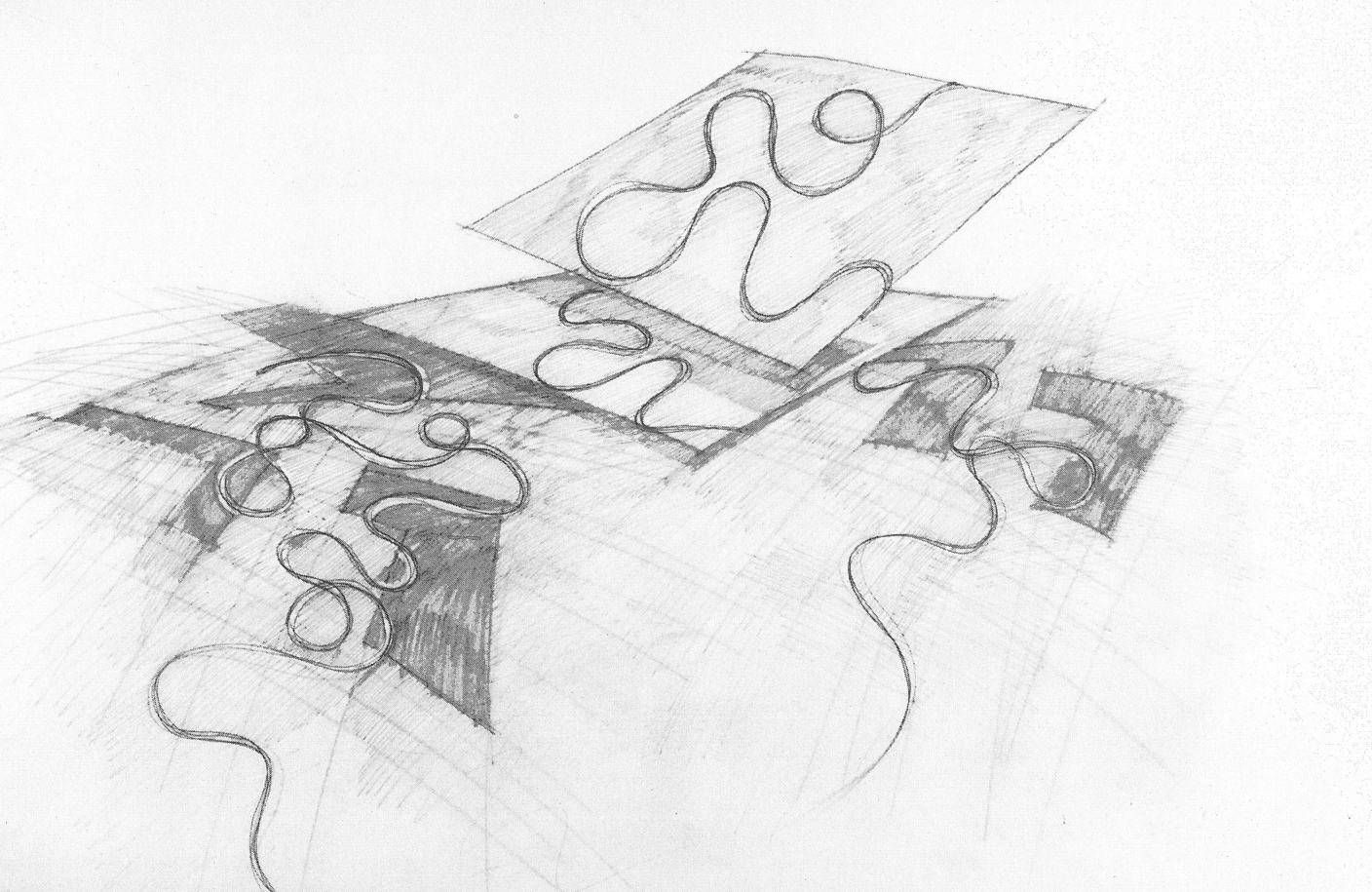

Griffiths, C.P, Analysis Drawing, Authors own work, 2013

Edward Robbins, formally lecturer in Urban Design at Harvard University and author of Why Architects Draw, makes clear the importance of the connections between society, culture and representation. He considers that drawing, in its many forms, provides the means by which architects interact with each other, the public and clients. Through representation landscape architects have the potential to enact change in the world. Robbins goes on to say “As part of the creation of design, drawing is about risk, vulnerability and the sharing of the most tentative as well as fully formed thoughts in a process that involves testing, critiquing, reiterating, and transforming.”4

Current thinking in landscape architecture is concerned with the perception of the city as a living, working, and changing organism, this releases the designer from a concept of landscape architecture in the city as provider of ‘nature’: parks, fountains, planters…an approach that is a cartoon, a stereotyped position and somewhat dooms landscape architecture to the sorting and placement of green stuff. This type of landscape architecture is perhaps not only the result of inadequate representational devices, it is also the result of more complex processes involving relationships between councils, clients, interdisciplinary teams and budgetary requirements. It could, however, be argued that thinking about the landscape as a collection of objects and applying this thinking through normative representational strategies hinders a more complex understanding of the landscape and its fluid and ephemeral nature.

Landscape architects need techniques that enable the unravelling of the multitudes of relationships between the constantly changing systems that exist within the city. The following section posits some techniques drawn from the discipline of fine arts that perhaps could enable the capturing of the ephemeral, for example, wave patterns, coastal processes, context, a work of art, a dance step, sound and light.

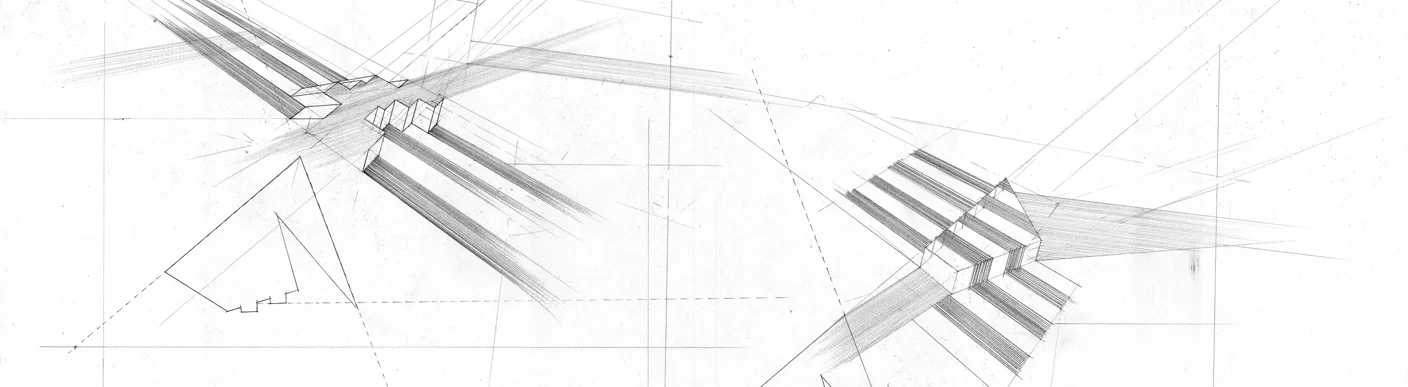

Griffiths, C.P, Analysis Drawing, Authors own work, 2013

Technique

Landscape projects often utilise transepts, analyse vegetation and are required to perform complex cut and fill calculations yet often the potential of this information is reduced to the image of that information, for example, the photograph of a native plant accompanied by the Latin and common names, a cross section that describes the shape of the land, or an aerial view of a large rural plot. The particular characteristics of the plant, its textural qualities, its growth patterns are far more interesting and rich. In the same way as levels of fatigue that the human body encounters when traversing a landscape made up of dips and hollows, or the processes involved in ploughing, sowing, reaping and distributing the crops or harvest from the rural plot, offer up deeper and more connected information to the designer.

It could be argued that one of the reasons that landscape architects have utilised the more image focused types of representational techniques is that these types of drawings determine how we build something; clients want to see what the landscape that they are paying for looks like. It is almost indisputable that these are important functions of the landscape architect and there is a time and a place in every project for these drawings, yet it could be argued that these drawings inhibit a creative and critical engagement with the landscape.

Rem Koolhaas opened his lecture in 1991 with the proclamation “architecture is a dangerous profession.”5Sanford Kwinter qualifies this statement in his essay Flying the Bullet, or, Where did the Future begin?6 “Architecture becomes dangerous when it forgoes all that is “pre-given” – in this case fixed types and predetermined matter – when, rather, it takes the actual flow of historical conditions as its privileged materiality (not just the discrete domains of geometry, masonry, stone, and glass), and works these, adapts these through transformations and deformations, in order to engender and bind its form.”7

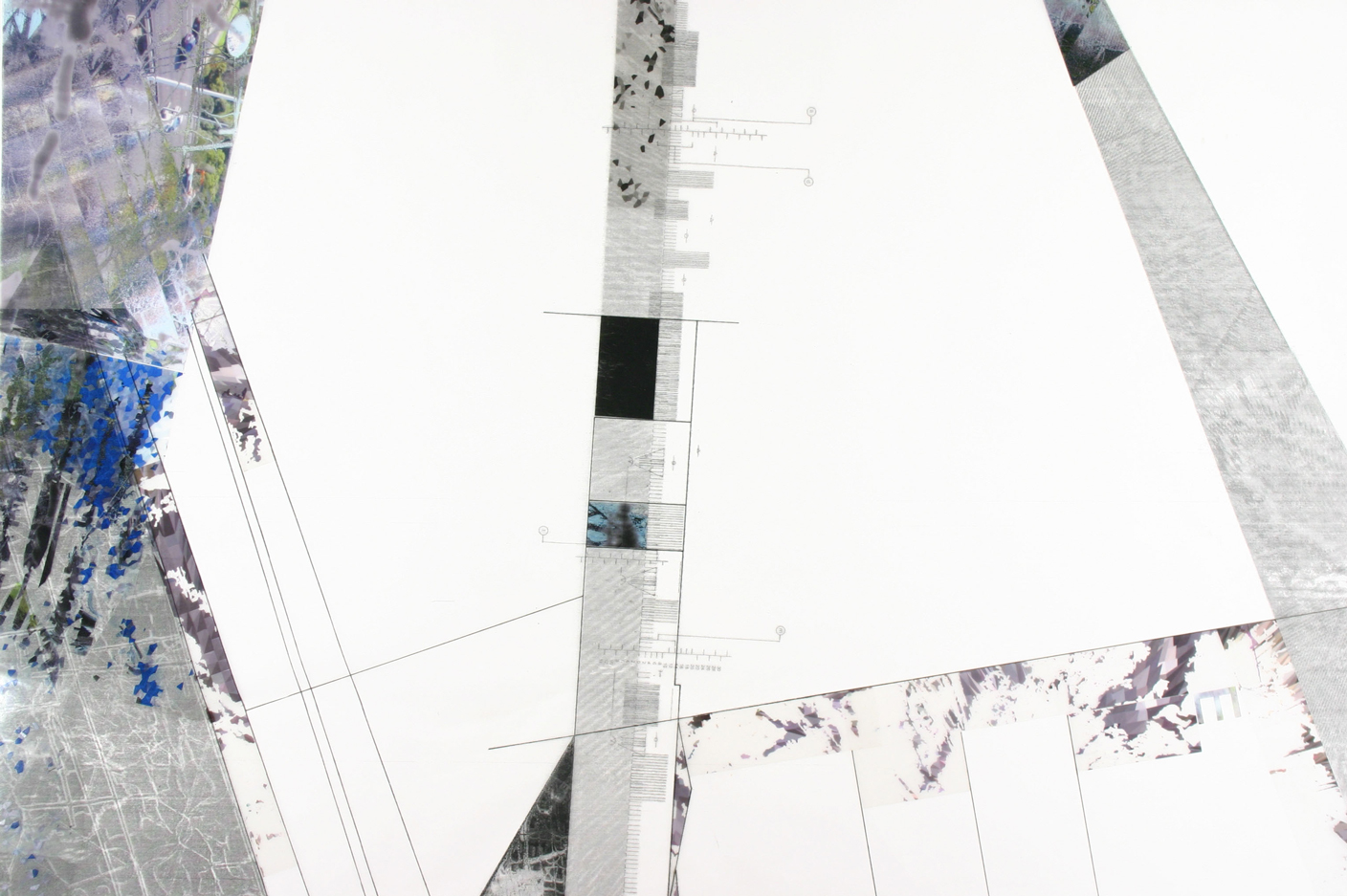

Analysis in landscape architecture could become, as Koolhaas describes, ‘dangerous’. Dangerous in the sense that experimental representations could uncover unexpected relationships. It can be argued that the way in which analysis is undertaken can influence the design process. The research machinery that is used to analyse contemporary landscapes includes Geographic Information Systems, iPhones, GPS, and Google technology, all highly evolved tools yet it seems a lost opportunity that these tools tend to focus on the recording of transport routes, open spaces, vegetation, landform, water flow etc. All of these are important, yet if we shift our inquisitiveness, and our tools a little, we may find that a different city emerges: one that is more concerned with processes of filtering, sorting, and redistribution: a contextual city, the way a city works.

Creative drawing methods including diagrams, collage, rubbings, and other mark-making allow an engagement with this contextual city, and provide access to the potential of landscapes, for example, the collected assemblage of the movement of sap, the up-take of water, leaf shed, and the growth rate of a tree, or the way a particular corner shop creates conditions that set up informal meetings and turns a footpath into an active social space, or the collision between steep sloping topography and a rail corridor. These contain a myriad of instructions other than the visual, which can be drawn out through a dexterous engagement.

Griffiths, C.P, Transfer Birds: close up, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.51

As mentioned above, in addition to the important and obvious conditions of landform and the proximity and abundance of water, landscapes are encoded with the ephemeral, the momentary, and with concepts of closeness and distance. These ephemeral and momentary intensities can be referred to as haecceities,8: the here and now of any given situation, the foregrounding of flux and movement rather than stasis. Landscape architects are used to looking at subjects, forms, shapes, and functions and tend to miss that it is an entire assemblage of the above that is a landscape: think of a horse, a rider, a dog, hunting, and a fox – these things together form a set of speeds and effects, a set of slowness and relationships9. Any one of these can be defined by isolating it, analysing it, and describing it, far more difficult, is to try to materially and formally understand the assemblage. Cities: roads, things, stuff, green, park, arcade are not apart from season, hour, date, wind.

Landscape design processes can be broken down into three broad phases: research, analysis, and design. It is in the analysis phase that poetic and creative recording techniques can often reveal important contextual relationships with the landscape. Two important factors in the recording of contextual information are first, the utilisation of Ali Rahim’s ideas of systemic delay,10 whereby any ‘concrete’ design moves are delayed permitting a move beyond ‘deterministic thought’ and therefore foregrounding creativity; and second, an operational approach is conducted within a representational scaffold, this enables any landscape element to become a building block in the design process.

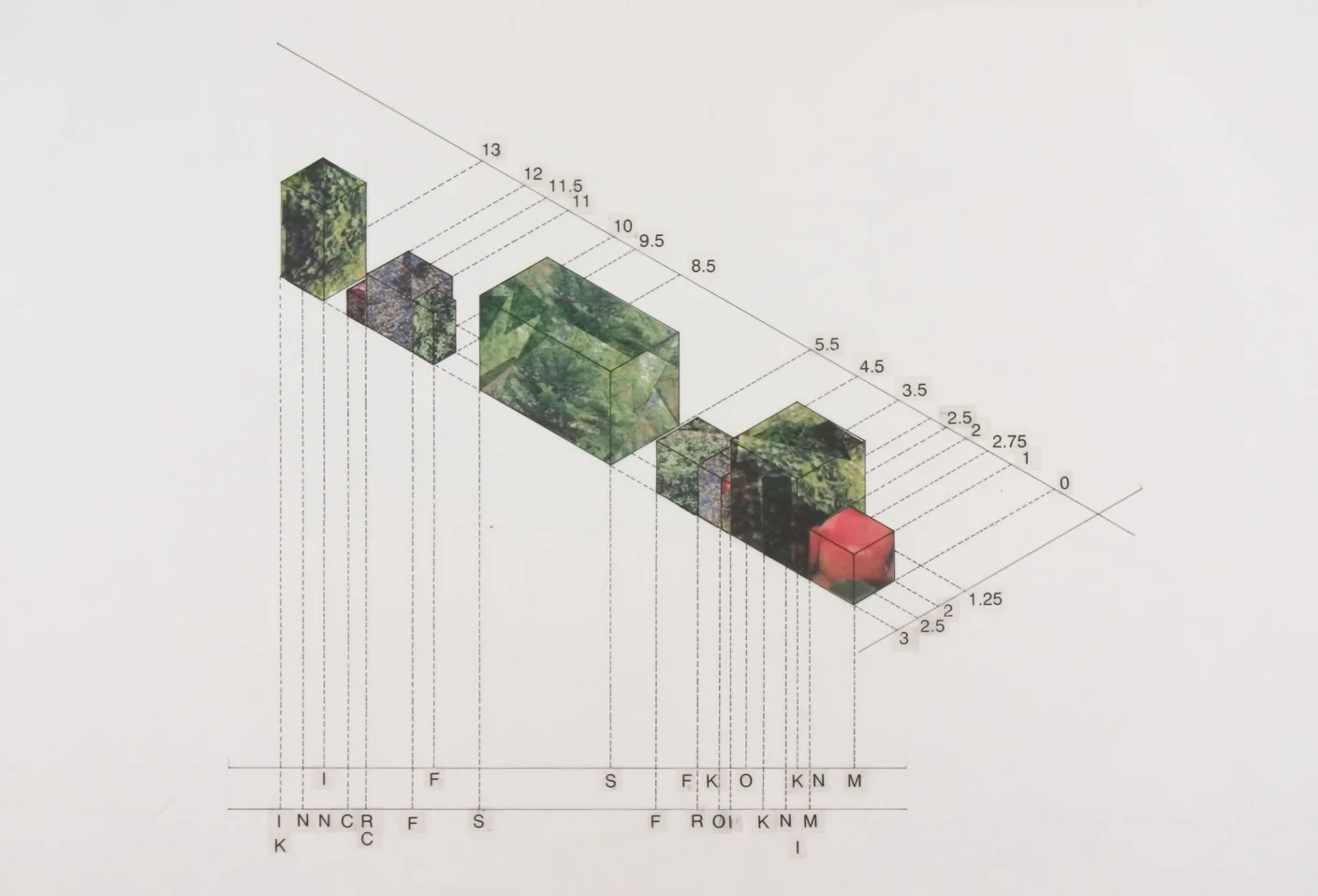

In adhering to these two ideas a basic structure can be manipulated to produce markedly differing forms, while retaining the same basic underlying code. Manual de Landa called this a ‘body plan’. He describes this idea as being akin to vertebrae that stretches across a site. The vertebrae are flexible enough to respond to different moments or events within a landscape situation, while remaining, strong enough to maintain its integrity. It provides a framework or scaffold within which are contained coordinates or points residing in space. Momentary events, for example the different growth stages of a plant, can be located within this scaffold and with the help of an operator, be allowed to shift around within it and indeed break out of the scaffold. Robin Evans argues in his book The Projective Cast that “What connects thinking to imagination, imagination to drawing, drawing to building, and buildings to our eyes is projection in one guise or another…all are zones of instability.”11

The use of operators also allows for the foregrounding of formation. They utilise verbs, for example, cut, gather, and fold to activate graphic material. This mechanism occurs as part of the first year architectural studios in the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and is outlined in the book Inchoate by architect Marc Angelil.12Operators permit the inclusion, into the design process of concepts that are either non-physical or that are just that, concepts.

Griffiths, C.P, Vegetation: growth rates and texture, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.26

Picasso utilised reproductions in order to understand the world in new ways, which led him to the works that he called variations. These were works he generated using other painters’ masterpieces as a starting point for his creative endeavours. Susan Galassi states in her book Picasso’s Variations on the Masters, “Taking others’ work as subjects for one’s own – to copy, elude to, or freely transpose into new creations – has long been a staple of art…artists from Vincent van Gogh to Francis Bacon freely transposed works by their predecessors...for Picasso…they were a continuous part of his creative program…Picasso invested variation with a vitality that bought it to the centre of his artistic endeavour, where the creative and the critical overlap.”13

In the same way that Picasso produced work in a step-by-step series where each painting referred only to the one immediately before and provided a significant abstraction from the original, landscapes can be treated in order to reveal the underlying codes and relationships embedded in them. Gallassi states that with variations “the structure or schema of the original is preserved”14 meaning that, whilst the resultant variations on the surface bear little pictorial reference to the original source material, they are nevertheless encoded with the structural characteristics. She goes on to say that “style, technique and most importantly, content undergo transformation.”15

Griffiths, C.P, Vegetation: growth rates and texture, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.26

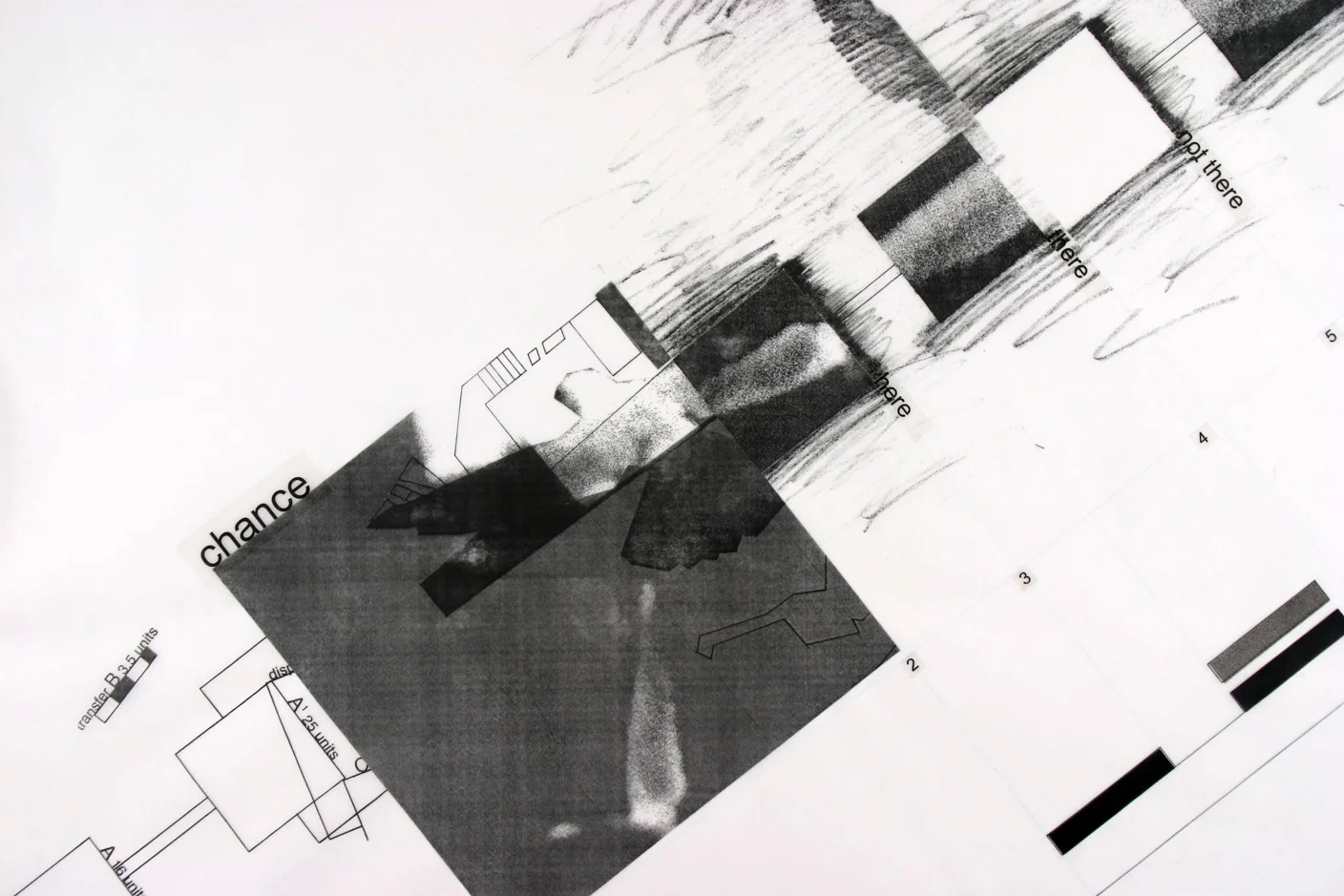

Another technique with which to understand the city is collage. This medium makes a number of constructive contributions to landscape architecture. One of the values of collage is its ability to rise above direct representation of elements, for example, in plan, section, and perspective drawings. Collage opens up new ways of exploring existing conditions and materials. It allows a certain freeing of the mind; any preconceptions about what elements physically look like and how they work are transcended and new opportunities arise, foregrounding the subjects’ qualities rather than concentrating on accurate, technical representation techniques.

Robert Motherwell, in an article called ‘Beyond the Aesthetic’ for the magazine Design, observed: “The sensation of physically operating on the world is very strong in the medium of collage, in which various kinds of paper are pasted to the canvas. One cuts and chooses and shifts and pastes, and sometimes tears off and begins again. In any case, shaping and arranging such a relational structure obliterates the need, and often awareness of representation. Without reference to likenesses, it possesses feeling because all the decisions in regard to it are ultimately made on the grounds of feeling.”16

In the discipline of fine art, collage has contributed to the expansion of the language of art and allowed a greater formal diversity and an increased expressive range.17Georges Braque (1882 – 1963), Picasso, and Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) were some of the early exponents of these media techniques. Collage has potential as a useful tool for landscape architects, specifically because of its ability to increase the expressive range of the designer. Diane Waldman states, “The technique of collage is ideally suited to the capture of noise, speed, time and duration….”18

Collage has the potential to do this because found images are already coded with chromatic information, textural information, various tones, marks, and forms. Without having to make these graphic decisions, the designer is free to concentrate on revealing the hidden or the elusive context.

Collage also allows layering of information, it is able to be continually ripped up, reworked, and reconfigured, each addition, or change, contributes to its configuration over time. It has an ability to capture the ‘commonplace’, actual conditions and inherent qualities. Further, “collage has often emphasised concept over end product; it has stressed the meaning of process; it has bought the incongruous into meaningful congress with the ordinary and given the commonplace, the ordinary, a magic of its own.”19

Variations and collage are techniques that can be used to capture the moments that regularly occur, but are often overlooked in the landscape. These moments contribute to a contextual understanding of how landscapes actually work. Take the two archetypal styles of theatre; the Italian style where the stage is a box that contains backdrops that create the illusion of distance and perspective; and the Shakespearian style of theatre where the stage juts out into the audience so that everyone who views the theatre sees something different. What if site information could be articulated in this alternative multi-dimensional way?

Hockney gives the example of two images: one a painting by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684 – 1721), entitled The Intimate Toilet c. 1715, Private Collection, and the other a Picasso, Femme Couchee 1932, Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée de l’Art Moderne, Paris. “In the Watteau painting you are an onlooker – it is as if you are looking surreptitiously on from another room, however with the Picasso, because you can see the back and the front at the same time, you were essentially inside the painting….”20 The Cubists, particularly Picasso, and the Abstractionists were exponents of these concepts. In the analytical phase of Cubism we find evidence of the painter dismantling objects and having analysed them into component elements rearranging them in a new order. This new articulation reiterates the sentiments of the Abstractionists. The potency and relevance of this new articulation is reinforced by the Abstractionists’ belief that no imitation can ever reflect the strength and beauty in the appearance of nature. In order to depict nature fully we must find another way.21

Griffiths, C.P, Bird Variations, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.31

Conclusion

Landscape architecture is well suited to contribute to this many-faceted, multidimensional discourse, which is generally centered on ways of designing. The landscape is encoded with the ephemeral, the moment, intensities and forces. Looking at landscapes from the bottom up, or upside down, enables a different viewpoint. By eluding familiar form and by viewing the landscape apart from its usual connections to objects and materiality, a new clarity becomes apparent, in much the same way as when drawing, if the concentration is focused on acute observation of the subject, rather than on thinking ‘can I draw?’ the outcome is startlingly competent.

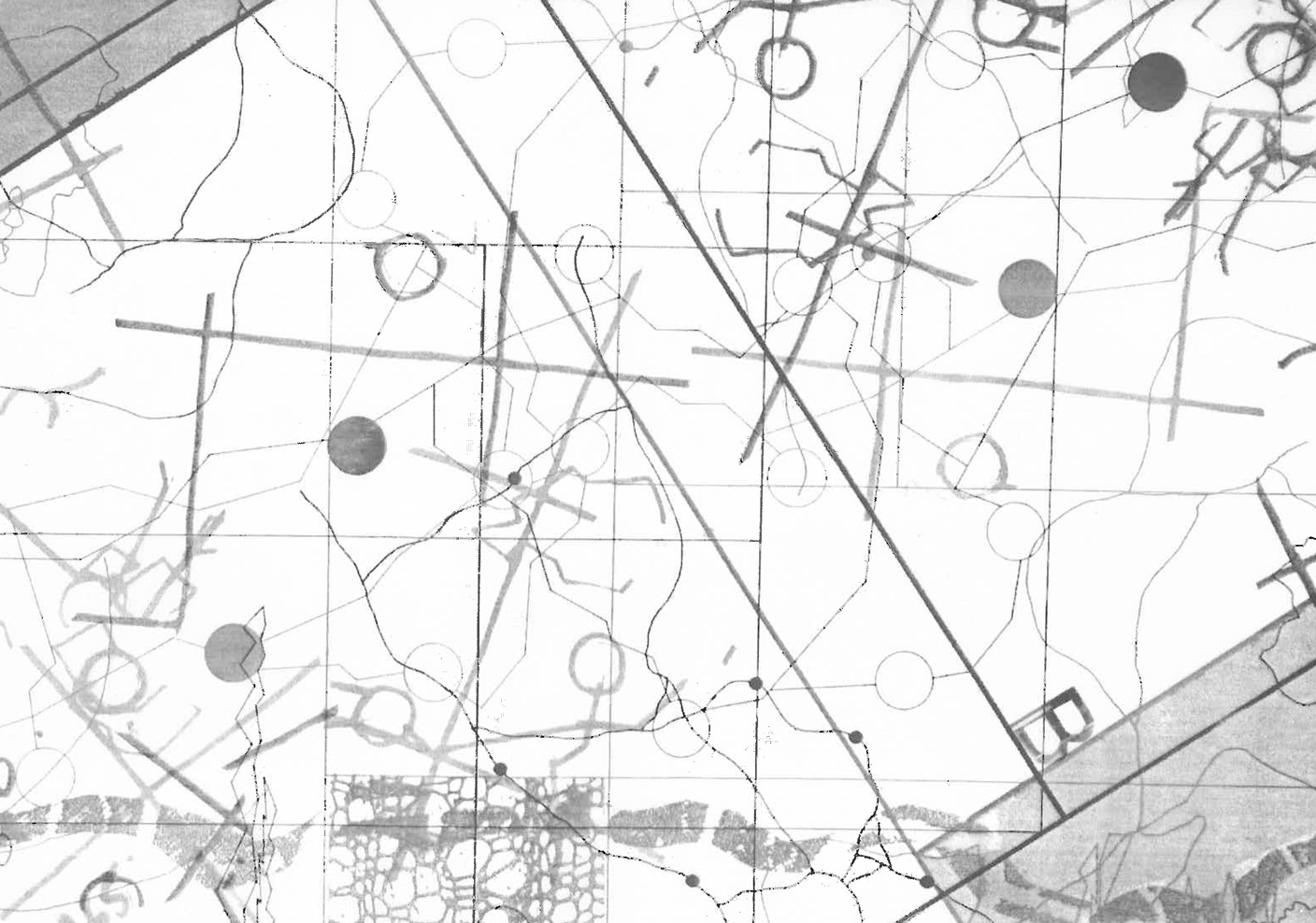

Griffiths C.P, The City 2, Authors own work, 2001.

This cognitive shift enables preconceptions about the landscape to be downplayed and ways of analysing the landscape to be enhanced.

Images that are stylised, abstracted, and distorted can often be dismissed as not being like the world, because they don’t look like the world. It is easy to hold up a photograph and say, ‘see, this is what it looks like’. However, this allows only one viewpoint, one angle, perspectival rules, and the concept of outside looking in. Drawing the landscape offers other ways of interpreting and understanding the forces and flows that are functioning in and through a landscape situation.

The techniques discussed in this paper have been derived from the discipline of fine art. The fine arts offer the freedom to be abstract, intuitive, and experimental, whilst still having a deep theoretical underpinning. Landscape’s agenda is unique. It has the capacity to utilise the freedom most often associated with art because it deals with itinerant and changing conditions, yet it also has a public responsibility to deliver purposeful outcomes. This project attempts to utilise the freedom of art in order to deliver ways of analysing that reflects the variable nature of landscapes.

The above techniques enable designers to distinguish between the pattern of organisation of a system and its physical structure, and to work with the former without becoming distracted by the latter. They allow for design investigations to be part of something bigger than one single solution for a site by going beyond subject matter that we can categorise, and therefore beyond ‘concrete’ form.

Issues of representation are not just about what colour, what pen or what paper, they are in this contextmore about what techniques can be employed that will allow the capturing and then the transformation of information that is pulsing through the city…therefore perhaps enabling designs that are more closely linked with the city.

Griffiths, C.P, Analysis Drawing, Authors own work, 2013

Griffiths C.P, The City, Authors own work, 2001.

Griffiths, C.P, Transfer Birds: close up, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.51

Griffiths, C.P, Vegetation: growth rates and texture, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.26

Griffiths, C.P, Support Variations, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.38

Griffiths, C.P, Bird Variations, from Reframing the Given, Landscape Analysis Techniques, VDM Verlag Dr. Muller, 2008, p.31

Griffiths C.P, The City 2, Authors own work, 2001.