Wetlands: A Diminishing Resource

This article by Gordon Stephenson was originally published in The Landscape - Journal of the New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects Inc. AUTUMN 1985.

Concern about the state of New Zealand’s wetlands has been simmering for decades. Drainage and development have decimated once extensive areas of lowland swamps, and indeed much of our finest farmland was once the home of bitterns and fernbirds, eels and mudfish, raupo and kaihikatea. Soon we would have only very scattered remnants left, unless some effective action was taken.

There had, over the years, been reports, articles, management guidelines and official publications almost too numerous to list, but firm progress was lacking. Thus it was in May 1982, Dr Ian Shearer, as Minister for the Environment, asked the Environmental Council to:

- assess the present overall state of wetlands, past and future trends

- identify the diverse objectives for the management of wetlands

- summarise present policies for wetlands and peatlands

- pinpoint deficiencies in the present situation

- formulate policy options and critically examine them for their effects in both short and long term

- indicate preferred options

- identify actions that could be taken in the light of preferred options

Six of us were assembled to prepare a report to be presented to Environmental Council. The first step was to call for public submissions. These made fascinating reading, revealing an unexpectedly strong determination to conserve our remaining wetlands, not only voiced by the "greenies" among us, but also by officialdom, national organisations, and even commerce. Only a handful (less than 5 out of the total 49) submissions implied they wanted the "status quo" in terms of policy, to remain.

We then undertook a week's tour of South Island wetlands. For me, a total layman where wetlands are concerned, this was an eye-opener. We trekked across bogs, pushed cars through a snow-bound Arthur's Pass, and puffed up Mackenzie Basin hills in a biting wind, and the knowledge and enthusiasm of my fellow travellers awakened a whole new arena of interest. The others in the group were Bernard Card, then chief pastoral lands officer for the Department of Lands and Survey; Professor Alan Mark, botanist and notable conservationist, University of Otago; Dr Roger McLean, geographer with special interest in coastal and estuarine areas, University of Auckland; Keith Thompson, wetland specialist, University of Waikato and Bob Priest, soil conservator and administrator, Waikato Valley Authority.

After South Island, we separately visited many other wetlands, and spoke to innumerable organisations and individuals, and started writing.

What did we find? I quote from the report.

"The problem with wetlands is that they are rarely seen as beautiful scenery. They are often difficult to walk across, and so are rarely visited. Their wildlife is usually secretive, their plants not spectacular or flamboyant. Their values as a source of mined material or as pastoral land or for horticulture are only apparent after the wetland has been irreversibly destroyed. Their facility to assist in water control is often only recognised as we lament both floods and water shortages following their development."

''There is not much wetland left, certainly very little in its natural state. It is not only the overall quantity that is reduced. There are many distinctly different types of wetland, all with their special values, and some are now very scarce indeed."

When we came to examining future options, we decided that "it is this problem of arriving at satisfactory policies for a resource, most of which has been destroyed, that have necessarily meant … a greater emphasis (in the report) on the case for protection, since the policies and techniques for development are well established."

It was very clear that the status quo policies would lead fairly soon to a near-extinction of the wetland habitat. In fact, it was only a question of time-scale between retaining existing policies, and an option based on full development.

On the other hand, complete preservation was unworkable. There was no inventory of wetlands, and many wetlands were half-way through development projects, and irretrievably damaged.

We therefore recommended a series of actions to ensure "... management through appropriate policies devised from an inventory, classification and evaluation of all wetlands." This recommendation has been actioned, and an inventory of some 2500 wetlands is complete.

We drafted a policy document for adoption by Government. The objective was to ensure "a consistency of policy among those with public responsibilities that affect wetlands." This document, re-drafted and extended, and after wide circulation, was submitted to the previous Government in May 1984. The election deferred action. The new Government is now considering it, and one hopes by the time this article is read, it will have been accepted.

We requested that a moratorium be placed upon development of all Crown wetlands, pending completion of the inventory. This was done.

Because many wetlands are in private hands, their protection depends on a whole range of laws and regulations, from the Town and Country Planning Act, to the Water and Soil Conservation Act, and on the attitudes of a host of individuals and organisations. We found that under present legislation, very little indeed can be done to ensure protection on private land, as Mr Justice Turner noted in a recent planning decision. The need for a water right may not apply, and if it does, it is legally difficult to refuse one. We therefore recommended some minor amendments to both the Town and Country Planning Act and the Water and Soil Conservation Act.

We examined the role of some 22 organisations and departments with an impact on wetlands, and suggested actions each should take.

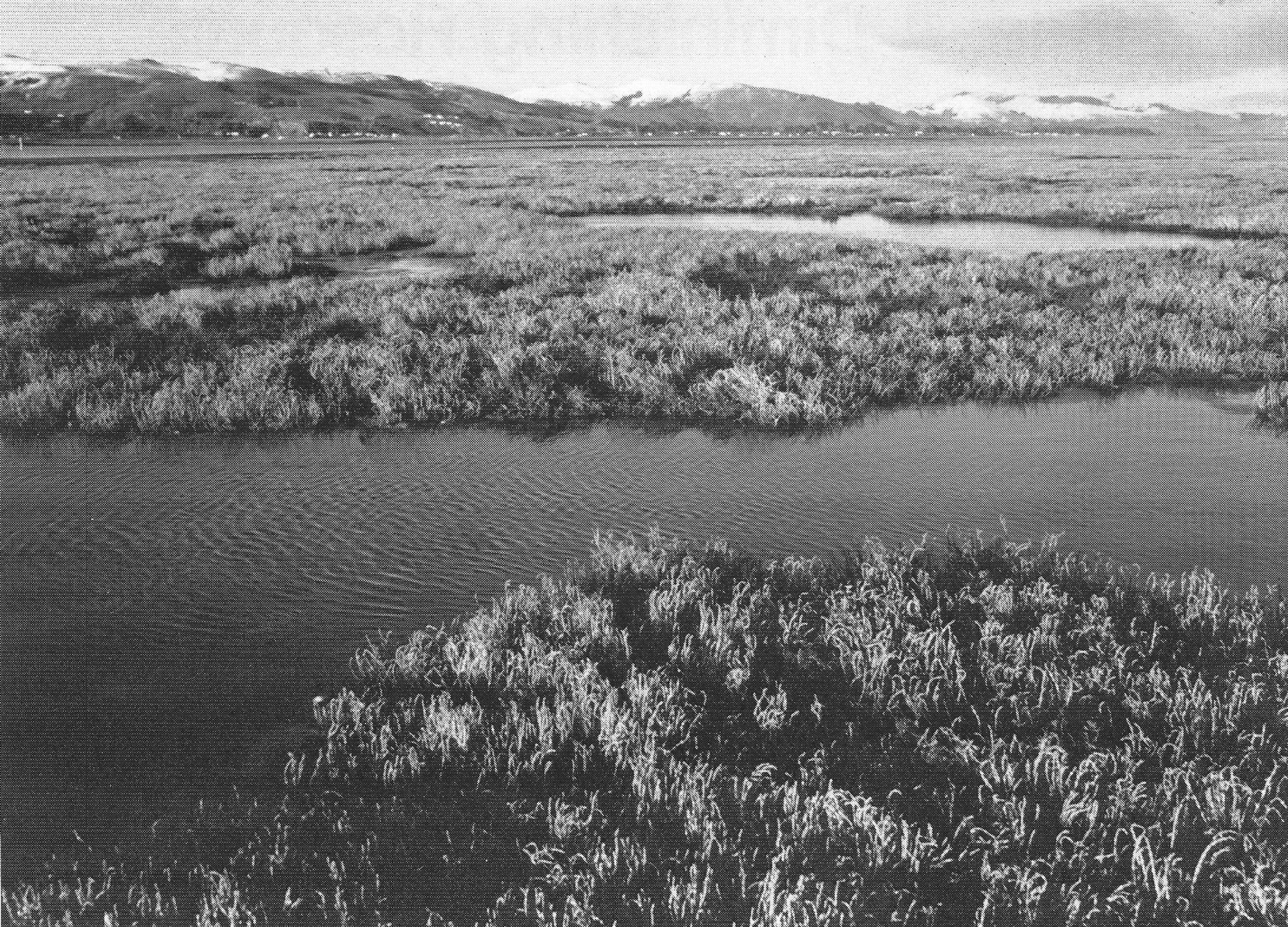

Aramoana Salt Marsh, Otago. The 225 hectare inter-tidal, salt marsh, and wetsack wetland is near the entrance to Otago harbour. The proposed aluminium smelter was to have been adjacent. Considered to be the best salt-marsh south of Nelson, it is an important habitat for wading birds, a rich feeding ground for fish at high tide, and supplies large quantities of detritus for bottom-feeding fish. Saline wetlands occur along several parts of the coast. Damage to them can influence stocks of commercial fish like snapper. The wetslack or marginal parts are particularly valuable botanically, but are also the most susceptible to damage from grazing and changes in water supply.

We were determined at the outset on two things. One, that this should not be "just another report" to be shelved, but that it should lead to action; and two, that it should be written in a manner that anyone could understand, with its message clear and unambiguous. We therefore included a large photographic section, with captions that amplified and illustrated the messages in the report.

The report was initially published with help from the Acclimatisation Societies, the Queen Elizabeth II National Trust, and Department of Lands and Survey. It was subsequently reprinted by NWASCO as Miscellaneous Publication No.58.

It was received by Environmental Council, who followed-up the many recommendations.

Let us hope that another report on our even further diminished wetlands will not be needed in 10 years time.