Quality Urban Design Suburbs for Auckland

Auckland’s suburbs need quality urban design[i]. This is important as our largest urban centre is rapidly increasing by 40,000 people a year, through natural population increases and unprecedented immigration. This is similar to a small town the size of Whanganui arriving in Auckland each year. Estimates are that to accommodate this growth Auckland will need anything from 13,000 to 30,000 new houses[ii].

Last year Auckland’s average house price topped $1 million and rents rose 4.4 per cent, to an average $524/week.[iii]. This has resulted in an alarming lack of safe and affordable housing for people on low wages or on benefits. Homelessness is at figure most New Zealanders have never seen before[iv]. The combination of high house prices; high rent; insecure tenancies and high homelessness are all part of a growing housing crisis.

I do not believe the answer to Auckland’s housing crisis is through increasing the supply of greenfield land on the edges of our towns and cities, commonly known as sprawl or more politely called ‘dispersed neighbourhoods’[v]. These neighbourhoods are economically, environmentally, socially and culturally expensive to create and live in.

Measures to increase housing numbers through dispersed neighbourhoods have often created perverse results such as higher land values. The implementation of the Special Housing Areas (SHA) [vi] legislation in Auckland increased land value by incentivising land banking and on selling rather than building houses. The new Auckland Unitary Plan has up-zoned large amounts of greenfield land and as a consequence has further increased land value in these areas. In just one example Auckland Council is grappling with the increasing costs of purchasing land for infrastructure and social infrastructure within and around the Whenuapai Structure Plan[vii] area.

Expensive and complex new infrastructure issues for waste-water connections face west Auckland’s new dispersed neighbourhoods. Parts of south east Auckland’s future urban zone may never be developed due to the complexity, expense and social costs of building on old peat swamps where significant flooding will regularly occur each year. Northern Auckland’s future urban zones need comprehensive public transport systems (surely light rail if not heavy rail) to network the suburbs, increase transport modes and reduce the reliance on private cars. All these new infrastructure costs will be complex, expensive and take considerable time to construct.

For the dispersed neighbourhood dweller there are further transport issues to contend with including longer commutes to the city centre, limited public transport connections, limited social infrastructure facilities, and lack of diverse job prospects in easy commuting distance. In dispersed neighbourhoods people will use their private car more, their commute times will be longer and their transport costs will be higher. That easy 30 minute commute to work ten years ago is now a horrendous hour or even two hours. Consider what it will be like in 40 years? Statistics show that the farther a house is out from a vibrant city centre the more its owners are likely to face mortgagee foreclosure during a financial crash[viii]. More positively the chances of mortgage sales are reduced by having more public transport options that reduce transport costs[ix].

Social cost are also high for the dispersed neighbourhood dweller. A Swedish study found people who endure more than 45 minutes commuting time were 40 percent more likely to divorce[x]. Urban distances change social networks with family and friends and they are more likely to be further apart with long leisure time drives to see them[xi]. With longer commutes people are less likely to know or trust neighbours, therefore becoming socially isolated.[xii]. From my own experience commuting by car means I only get to know my immediate neighbour and flatmates. But when commuting by public transport I get to know people of the neighbourhood and discover the local happenings. The more connected you are with adult friendships the more your children are insulated from the effects of parental stress, you sleep better, you tackle adversity better, you live longer and in the words of Charles Montgomery ‘you are happier’[xiii].

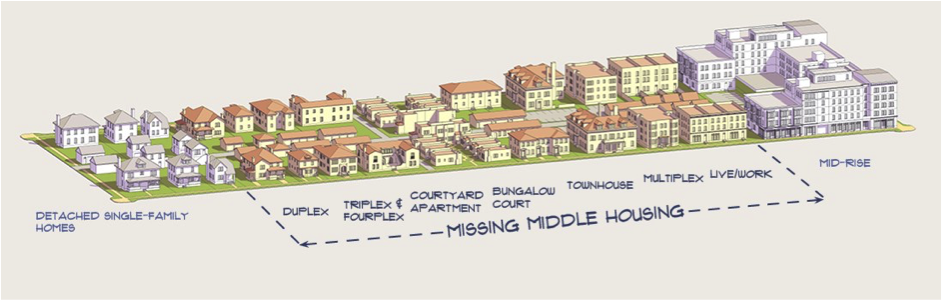

I believe the answer to Auckland’s housing crisis is to create quality medium density[xiv] suburbs through intensification of our existing suburbs. This is a shift to reinvent suburbia. It will need new sustainable housing, additional infrastructure and social infrastructure, improved public transport to reduce commuting times and improved walking and cycling infrastructure. Ultimately it should enable us all to become happier[xv]. In America this medium density is often referred to as the ‘missing middle’[xvi]. A commitment to create quality (the adjective meaning ‘good quality’ or ‘excellent’) suburbia, that is fit for purpose and exceeds the suburban dwellers expectations is required by Central Government, Auckland Council, developers and the community.

Figure 1 The Missing Middle is a made up of different multi-unit town houses or small apartment compatible in scale with the standalone house creating a more walkable suburban neighbourhood.[i].

Under the Auckland Unitary Plan infill has been made easier within the Single House Zone. It is permitted to convert a principal dwelling (existing on or before the 30 September 2013) into a maximum of two dwellings or a minor dwelling not exceeding 65m2 floor area is permitted on a site. Both these measures in themselves could create considerable numbers of future houses. The majority of people at a recent home show in Auckland were very interested in the additional minor dwelling for their older relatives or married children.

It is worth considering the different built forms of existing suburbs to analyse how they could be intensified. The low density suburbs designed over 40 years ago in the 1970’s are made up of stand-alone moderately sized 120m2, three to four bedroom homes, on a quarter acre (1012m2) section with a building site coverage of a very low 11.85%[i]. The 1970’s house surrounded by a large swathe of grass can be redesigned to accommodate far greater intensification with extra stand-alone houses or be totally rebuilt to accommodate increased intensification.

Figure 2 Te Atatu Peninsula house with one bathroom and three bedrooms on a 910m2 site. Now in the new Auckland Unitary Plan Terrace Housing and Apartment Zone considerably increased density of up to five levels (with Auckland Council approval)[i] is allowed.

The 2011 average sized house with its large house size of 210m2 (commonly referred to as McMansions[i]) on a smaller section of about 450m2 has a site coverage of 46%[ii] and could be intensified via internal subdivision. Quality conversions of the largest room in the house (the double garage) may be an acceptable way of adding smaller affordable housing units within a dwelling and provide income to an aging generation of home owners. The house may also be able to be totally split horizontally or vertically.

Figure 3 Albany a two bathroom 4 bedroom 237m2 house on a 537m2 site. The double garage visually dominates the house from the road suggesting that to get to services and social infrastructure you require a car. The garage is also the largest room in the house.[i].

Further intensification could occur on sections around 600m2 as shown in recent Tamaki Regeneration, Fenchurch Street (Figure 4) where five units have been developed. Large scale urban renewal within existing suburban neighbourhoods such as Talbot Park[i], Tamaki Regeneration[ii] and the future Northcote Development[iii] can create greater urban design flexibility however it is expensive, takes time and is very disruptive to the existing long term community. I will read with interest the latest Governments consultation document on Urban Development Authorities[iv] to see if the authorities are going to be set up to make positive change with a shared community vision[v] or focus on increasing houses and profits of the UDA partners.

Figure 4 Fenchurch Street, Glenn Innes in the Tamaki Regeneration area is offering 86m2 houses on 115m2 sites[i]. However the price of $795,000 is hardly affordable.

At the moment Auckland Unitary Plan is on the starting blocks with developers testing the waters to see what they can build and what their boundaries are. The Auckland Design Manual[i] has information on the best type of house for sites. In December 2016 volume 1 of the Single House Zone with a secondary minor dwelling was launched. This includes an easy guide to the Auckland Unitary Plan for each type of house type[ii]. These tools provide an important way of unpicking the Unitary Plan and creating information that everyone understands.

One issue that has not been resolved with the Unitary Plan is the number of suburbs with restrictive private covenants. As section sizes decreased development companies began imposing restrictive private covenants, under the Property Law Act 2007, to dictate the house size and restrict further subdivision[iii]. Restrictive covenants tend to reduce the diversity of housing sizes and limit housing affordability with only larger costly housing options being allowed[iv]. This is not a Resource Management Act or Building Act imposition but a burden imposed by developers. Councils therefore could spend millions of dollars on planning instruments to up zone land for urban intensification to have it thwarted by anti-subdivision covenants. Central Government needs to legislate that pubic planning instruments (District Plans) have the ability to override restrictive private covenants set through the Property Law Act 2007.

At the same time Central Government needs to set standards for minimum sizes of dwellings and rooms. Auckland Council is supporting minimum dwelling size and most banks won’t lend on dwellings smaller than 60m2. However further Government legislation on house and room size would be valuable in reinforcing the quality of all future residential suburbs.

Retrofitting existing low density to medium density suburbs will not be easy and mistakes and poor intensification will occur. However the present Auckland Unitary Plan provides the opportunity to consider new ways of intensification. New tools such as the Auckland Design Manuals guidance and case studies provides the opportunity to test and refine designs. The intensification of existing suburbs is of paramount importance to create quality suburbs fit for purpose today and for the next 40 years.

[1] Urban Design definition from the Ministry for the Environment (2005) New Zealand Urban Design Protocol. Urban design is concerned with the design of the buildings, places, spaces and networks that make up our towns and cities, and the ways people use them. It ranges in scale from a metropolitan region, city or town down to a street, public space or even a single building. Urban design is concerned not just with appearances and built form but with the environmental, economic, social and cultural consequences of design. It is an approach that draws together many different sectors and professions, and it includes both the process of decision-making as well as the outcomes of design.

[1] http://www.radionz.co.nz/news/political/324491/govt-slashes-housing-shortfall-figure-without-explanation

[1] http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=11800458

[1] Alan Johnson (2017) Off the Track. State of the Nation Report. The Salvation Army- Social Policy and Parliamentary Unit.

[1] Charles Montgomery (2013) Happy City –Transforming our lives through urban design. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[1]Housing Accords and Special Housing Areas Act 2013

[1]http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/EN/planspoliciesprojects/plansstrategies/Councilstrategies/Documents/whenuapaistructureplan.pdf

[1] Charles Montgomery (2013) Happy City –Transforming our lives through urban design. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Plus various other studies in Australia and New Zealand.

[1] Helen Viggers and Philippa Howden-Chapman Urban form, public transport and mortgagee sale in Growth Misconduct avoiding sprawl and improving intensification in New Zealand Edited by Karen Witten, Wokje Abrahamse and Keriata Stuart. New Zealand Centre of Sustainable Cities.

[1] 2011 study quoted in page 55 of Charles Montgomery (2013) Happy City –Transforming our lives through urban design. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[1] Charles Montgomery (2013) Happy City –Transforming our lives through urban design. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

[1] Ibid

[1] Ibid

[1] http://www.mfe.govt.nz/more/towns-and-cities/medium-density-housing “Medium-density housing means comprehensive developments including four or more dwellings with an average density of less than 350 m2 per unit. It can include stand-alone dwellings, semi-detached (or duplex ) dwellings, terraced housing or apartments within a building of four storeys or less. These can be located on either single or aggregated sites, or as part of larger masterplanned developments”

[1] Charles Montgomery (2013) Happy City –Transforming our lives through urban design. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

[1] http://missingmiddlehousing.com/

[1] http://missingmiddlehousing.com/

[1]Guy Marriage (2010) Minimum vs Maximum: size and the New Zealand House. 2010 Australasian Housing Researchers’ Conference

[1] http://www.realestate.co.nz/2942999

[1] "McMansion" is used here to denote a super sized, multi-story house that awards superficial appearance, functionality and sheer size, over urban design quality.

[1] Guy Marriage (2010) Minimum vs Maximum: size and the New Zealand House. 2010 Australasian Housing Researchers’ Conference.

[1] http://www.realestate.co.nz/3008615

[1] http://www.mfe.govt.nz/publications/towns-and-cities/urban-design-case-studies-local-government

[1] http://www.tamakiregeneration.co.nz/

[1] http://northcotedevelopment.co.nz/ and https://www.panuku.co.nz/northcote

[1] http://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/housing-property/consultation/urban-development-authorities

[1] https://www.sgsep.com.au/publications/best-practice-principles-urban-renewal

[1] http://www.realestate.co.nz/3007239

[1] http://www.aucklanddesignmanual.co.nz/

[1] http://www.aucklanddesignmanual.co.nz/design-process/UnitaryPlan

[1] http://www.hillyoungcooper.co.nz/assets/Uploads/Restrictive-Covenants-Mead-Ryan.pdf

[1] David Hattam and John Raven My House, My Castle in Planning Quarterly, September 2011, 32.